by Alejandra Edwards

Pitcairn Island, with barely 47 sq. km. (18.15 sq. mi.), is part of a group of four volcanic islands (Pitcairn, Henderson, Ducie and Oeno), located in the South Pacific at 2,086 km (1296 miles) from Easter Island. Its history is notable for various reasons. Firstly, for being the closest island to Rapa Nui, inhabited in the past and then abandoned, leaving archaeological remains in their wake. Secondly, for its few remaining inhabitants, barely 50, almost all descendants of Fletcher Christian and the sailors who mutinied on the British galleon HMS Bounty in 1789.

Many people think that the history of Pitcairn began with the arrival of the 9 mutineers of the HMS Bounty with 12 Tahitian women and 6 Tahitian men who accompanied them. Few know that these islands had been inhabited in times past and then abandoned, leaving archaeological remains in their wake. The mutineers found earth ovens and remains of houses almost intact and they supposed that Polynesian colonists had left Pitcairn barely 50 years previously. They also found stones with petroglyphs and four ceremonial structures (marae) with stone statues and caverns with skeletal remains. Captain Frederick W. Beechey, who visited Rapa Nui as well as Pitcairn in 1825, noted the similarity of the petroglyphs, ceremonial centers and statues of Pitcairn with those of Rapa Nui. Unfortunately, the only thing that has survived to the present day from a marae, or platform, on Pitcairn is the torso of a statue which is currently found in the Museum of Otago in New Zealand.

Polynesians must have lived on Pitcairn around 700 or 800 years ago, forming a single culture with the islanders of Rapa Nui to the east and those of Mangareva and the Tuamotus in the north-west. The dozens of obsidian and basaltic tools which were traded with the other Polynesian islands can be found as distant as Mangareva (526 km – 327 miles) and Katiu in the Tuamotu islands (1,889 km – 1174 miles). The stone adzes found on Henderson have been geometrically traced to the basalt quarry of Tautama on Pitcairn, while others were found on Mangareva, confirming that once there was an active commercial exchange between islanders which probably included the Rapanui. The Mangarevans called Pitcairn Island He Rangi, Kai Rangi and Mata ki te Rangi. This last name, oddly, is also one of the ancient names for Rapa Nui, which opens several questions on the origin of the first colonists of Pitcairn, with whom they mixed and toward which they finally migrated. This could also shed light on the land of origin of the Rapanui and their ancestry and the role that Mangareva played in all this, since their narrative folklore is very similar to that of Rapa Nui. (In the mythology of Mangareva, it was the spirit of Ranga Henua who traveled to Mangareva and its legendary founder was Hotu Atua, while on Rapa Nui the spirit was of the wise man Haumaka and the founding king was called Hotu Matua.)

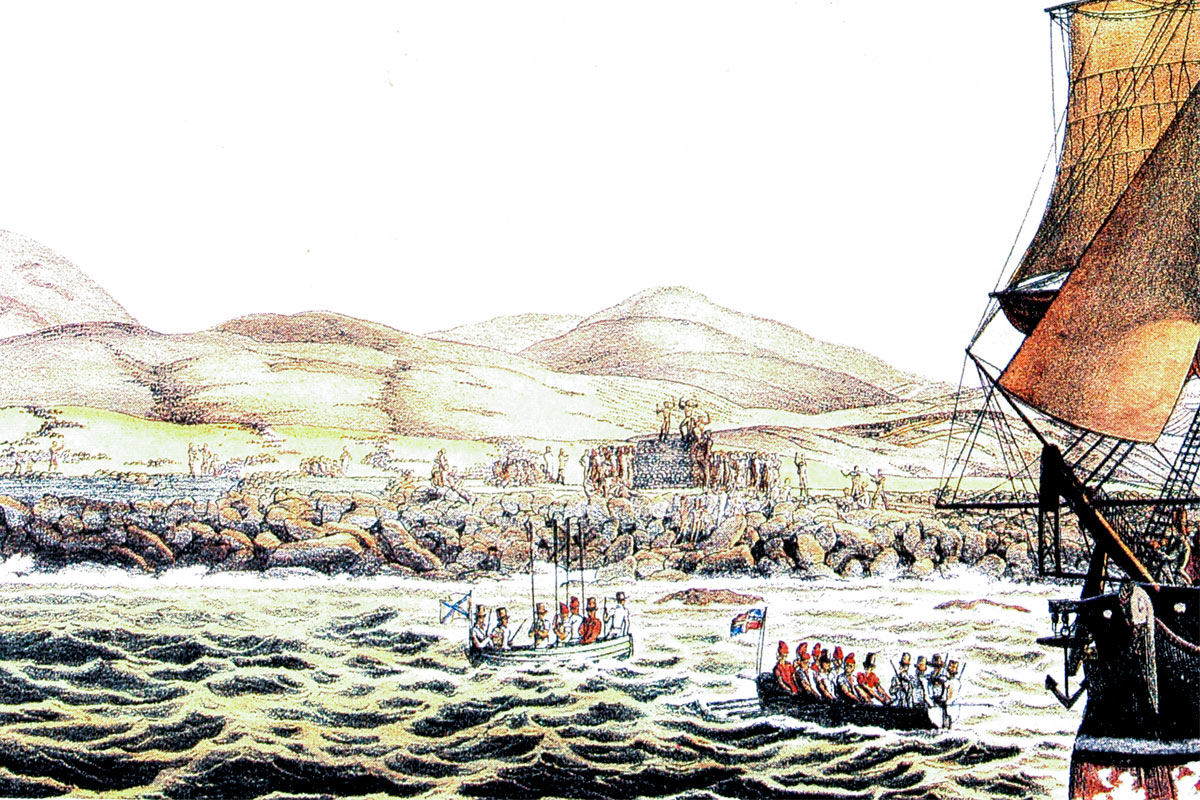

Back in recorded history, the famous British galleon HMS Bounty was sent to Tahiti in search of the breadfruit tree which was to be used as a supplementary food for slaves. Due to climatic reasons, it had to remain on Tahiti for half a year. It was April 28, 1789 when a greater part of the crew decided not to continue their voyage and mutinied against Captain Bligh, who was in command of the ship. Bligh was set adrift with crew who were still loyal, arriving eventually at the island of Timor, where the story became public. Meanwhile, Christian, accompanied by eight Englishmen, six Tahitian men and twelve Tahitian women, took over the Bounty and managed to settle with these people on this tiny enclave lost in the Pacific on January 15, 1790. Pitcairn had been discovered in 1767 by Captain Carteret of the Royal British Navy and given its name in honor of Robert Pitcairn, the son of a crewman who was the first to spot this island, which at that time was uninhabited.

The mutineers took great care not to be found. The Bounty was burned and sank into the Pacific. Although the colonists survived through farming and fishing, the initial period was broken by grave tensions and internal disputes, mostly caused by the lack of women. The male population was almost wiped out. By the year 1800, only one adult male remained alive – Alexander Smith, alias John Adams, the patriarch of the small community of nine women and nineteen children, who were educated in the most strict puritanism. Adams was pardoned by the British Admiralty for his labor of maintaining the children and died on Pitcairn Island at 65 years of age.

This small British colony has changed much since then. It is managed by an island council, a consultant body of ten members elected every year. The governor is the representative of the Queen of England. The only town and, therefore, the capital is Adamstown, located on the center-east coast of the island. In front of the courthouse is the anchor of the Bounty; the site of the wreck can still be seen in the waters of Bounty Bay. At the town church, there is also the Bible from the mutinied ship which was used as a guide for a new, peaceful society. The local economy depends on subsistence agriculture, which is now seeing the benefits of technological advances. A generator offers electricity during most of the day and the people move around from one side of the island to the other on motorcycles and scooters.

John Adams

Descendants of John Adams

The current population of Pitcairn fluctuates between 40 and 50 persons; they are strong, proud and incredibly ingenious and resilient. Most of them earn a living from the sale of crafts and the postage stamps that are printed with the story of the island, philatelic rarities that are in high demand by collectors, as well as from remittances from overseas investments. Metal launches give them access to passing cruise ships and freighters. Medical emergencies are evacuated to Mangareva. The children’s education is under the charge of an English teacher, but those whose wish to study at higher levels must do so in New Zealand. The entire population gathers once a year to harvest and process the sugar cane. They also celebrate important occasions, such as “Bounty Day” each January 23, when they burn replicas of the famous ship in honor of the day when Fletcher Christian sank the original.

Alexandra Edwards, the author, is currently organizing an expedition to Pitcairn in 2020 for the Pacific Islands Research Institute. The objective is to explore the site of the petroglyphs mentioned in this report, and also to join a crew for archaeological forensic tests in what is presumed to be an historical burial site at Adamstown.

Queen Elizabeth