Rapa Nui 1878-1888:10 years under a Tahitian Ruler

by Cristián Moreno Pakarati / Historian

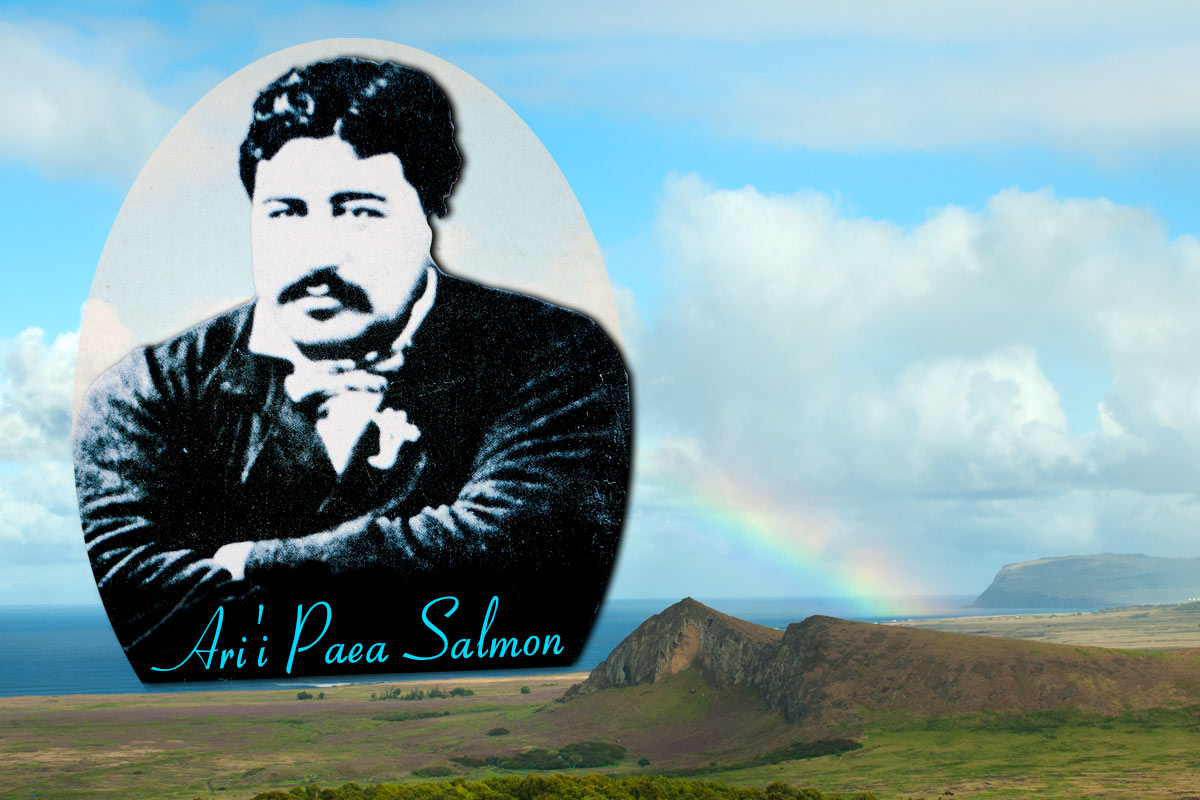

In 1876 the people of Rapa Nui were dispersed throughout many of the Polynesian islands with a few more than 100 souls attempting to survive on Easter Island. On Mangareva, a handful of Islanders were beginning to mix with the local population under the care of the Catholic missionaries. Larger numbers were to be found on Tahiti and Mo’orea, but they were held as a work force under harsh conditions in the sugarcane and coconut plantations of the Scotsman John Brander, owner of the firm Maison Brander. He had associated with a member of the Tahitian royal family: Alexander Salmon Jr., also called Ari’i Pa’ea for his noble title. The firm did business of many types throughout the Polynesian archipelago.

The person most responsible for the Easter Island diaspora was the French adventurer, Jean-Baptiste Onésime Dutrou-Bornier, who, after bringing the French Catholic missionaries to Easter Island on his ship, decided to establish himself there and start raising sheep for the wool which could be exported to Tahiti. This brought him into a business association with Maison Brander. He married a native Easter Islander and had two daughters, while declaring himself the king of the island. He was able to trick the natives into selling him their lands and exiled the most difficult ones to the plantations of his partner in Tahiti. His conflicts with the missionaries led to their abandoning the Island for Mangareva with many of the parishioners going with them. Finally, his constant abuse of power led to his death in August of 1876 at the hands of a group of natives.

The death of the owner of Maison Brander in Tahiti was the beginning of long legal battles to resolve the inheritance and heirs’ rights. A Chilean who had been living in Tahiti, Juan Chávez, arrived on Easter Island as the representative of the Tahitian firm and to take possession of the Island. Chávez installed himself in the manager’s house in Mataveri and threw out the widow and mixed-blood daughters of Bornier. He also took over most of the properties that the Catholic Church still held and claimed their plantations and animals. Chávez didn’t last very long on the Island. After spending a long periods trapped in the house with his family and never letting his guns leave his side for fear of a destiny similar to Bornier, he was probably very relieved when the ship came to take him away in October of 1878. Arriving on the same ship was his successor, Alexander Salmon, Ari’i Pa’ea, who had decided to take charge of the business on Easter Island himself.

Salmon didn’t arrive alone. He came with several returning Easter Islanders and some 20 Tahitians to handle the most important work on the ranch. The arrival of these other Polynesians created a new cultural impulse for an island that had seen its population severely diminished by the Peruvian slave raids and the subsequent epidemics in the late 1860s. The sudden disappearance of an enormous amount of people caused a tremendous loss of collective knowledge, traditions and ancient skills. The Islanders tried to replace the loss by incorporating and adapting that brought by the new arrivals. Thus, the British-Tahitian, as the leader of the group, became an important figure in the local society, which at that point held 170 inhabitants.

Unlike Chávez, Salmon established convivial relations with the Easter Islanders. As an experienced businessman, he began to encourage the Islanders to develop some commerce with the ships that called at Easter Island and, at the same time, gave impulse to the livestock production. While on one hand he stimulated native wood carving, to the point that some of that work is today found in the great ethnological museums of the world, on the other, he destroyed great megalithic monuments to build fences and corrals for the ranch. In this period, Salmon moved his base of operations from Mataveri to Vaihū, which he bought from the Catholic Church in 1884. He raised the English flag and offered sovereignty to Great Britain, without receiving any response from London.

In 1886, Alexander Salmon played a major role in the American expedition of the USS Mohican, serving as an informant and assisting William J. Thomson. Thomson’s later publication is one of the most well known and, to date, important ethnographic studies of the Island in that period. Cooke, the surgeon of the USS Mohican, noted: “Mr. Salmon, who is guide, philosopher, and friend to these people, unites in his person (and being a giant in stature, he can well contain them) the duties of referee, arbiter, judge. They entertain the greatest respect for him … look up to him as their master; go to him with all their troubles. His word is law, and his decisions final and undisputed.” This was, without a doubt, a period of strong Tahitian influence in the local language and culture.

Finally, in 1888, Alexander Salmon was the translator and connection between the locals and the Chilean representatives, Policarpo Toro and the officers of the ship Angamos, in the signing of the famous “Agreement of Wills” with 12 Rapanui chiefs for the annexation of the Island to the nation of Chile. Toro had already signed a contract in Tahiti with Tati Salmon, the older brother of Ari’i Paea, purchasing the Salmon properties on Easter Island and a promissory note with the son of John Brander for the family’s lands which were still in litigation. Alexander Ari’i Pa’ea Salmon Jr. signed the “Agreement of Wills” as a witness, leaving his name in the history of Rapa Nui, and then left Easter Island for Tahiti on December 14, 1888. In 1895, the courts in Bordeaux, France finally resolved the conflicts of inheritance around Maison Brander, finding in favor of John Brander, Jr., who, eleven years later decided to sell his Easter Island holdings to Enrique Merlet, a French businessman established in Valparaiso, Chile.