Elite Control and Exchange of Archaeological Stone on Rapa Nui

by Dale F. Simpson Jr. – Arqueólogo / Archaeologist

University of Queensland, School of Social Science (Archaeology); College of DuPage (Anthropology);

Manu Iri Heritage Guardians; Ka’Ara Environmental Conscience.

In the early stages of my Ph.D. fieldwork about Rapa Nui’s ancient basalt sources, quarries, workshops and artifacts, I portrayed the prehistoric Rapanui as ancient geologists and prolific miners, who developed multiple reduction sequences to create fine-grain basalt tools and feature-stones from five areas: Pu Tokitoki, Ava o’Kiri, Rano Kau, Vai Atare, and the south coast mines found between Hanga Poukura and Hanga Hahave (Moe Varua, May 2015). I suggested that the demarcation of fine-grain basalt quarries and sources with Make-Make petroglyphs was an attempt by chiefly and elite retainers to oversee and control important basalt sources, and conceivably limit the access and use of these important lithic (stone) quarries. Since this initial report, I have furthered my research and have arrived to some preliminary conclusions about sociopolitical interaction of the prehistoric Rapanui culture.

My research is based on the geochemical fact that every lava flow on Rapa Nui is like a finger, with its own “rock D.N.A.” and elemental autograph; therefore, each artifact made from a specific quarry can be identified from the flow’s unique geochemical fingerprint. From here, we can trace the movement of material – from geological sources to archaeological sites – to identify if certain social groups were using certain stone, controlling certain quarries, and/or extracting specific material for specific tools. With this information, we can evaluate and hopefully corroborate and/or disprove previous interpretations of the island’s prehistoric sociopolitical organization and territoriality. Geochemical results suggest:

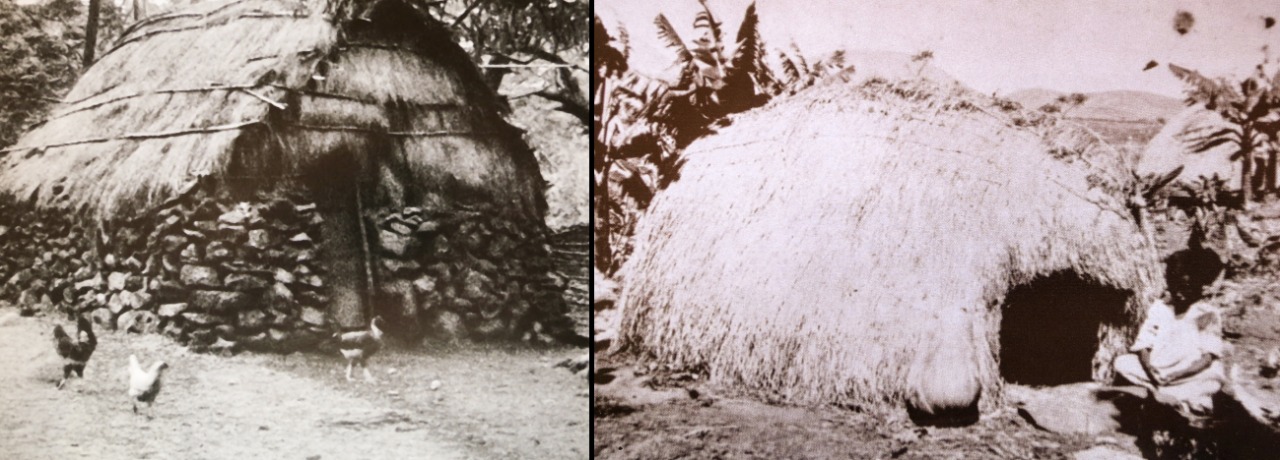

1) Basalt resources from Rano Kau and Vai Atarewere hardly, if ever used for tool manufacture. Instead, stone sources and quarries from these areas were utilized to extract keho (flat basaltic laminates) used for house construction in Orongo. Moreover, basalt used to make lithic tools found in the Vai Atare region were not even sourced locally, but were provenanced to the southern coast mines.

A remaining question however, is which were the social, political, and economic mechanisms that facilitated this movement of basalt? Was it a form of exchange like bartering between elite, where each mata produced resources afforded in their mata kainga? Some exchanging, for example, horticultural crops for stone, plant and animals resources for stone, and/or people and information for stone. Was there a system of so-called trade between mata and even within a single mata kainga? These are questions I am still very much interested in, and future analysis and publications will assist in illustrating the sociopolitical economic complexity of the prehistoric Rapanui culture. (“Rapa Nui Geochemical Project” –Twitter & Facebook: @RNgeochemPHD).