Educator, musician, and guardian of the ancestral language

by Consuelo Martinez

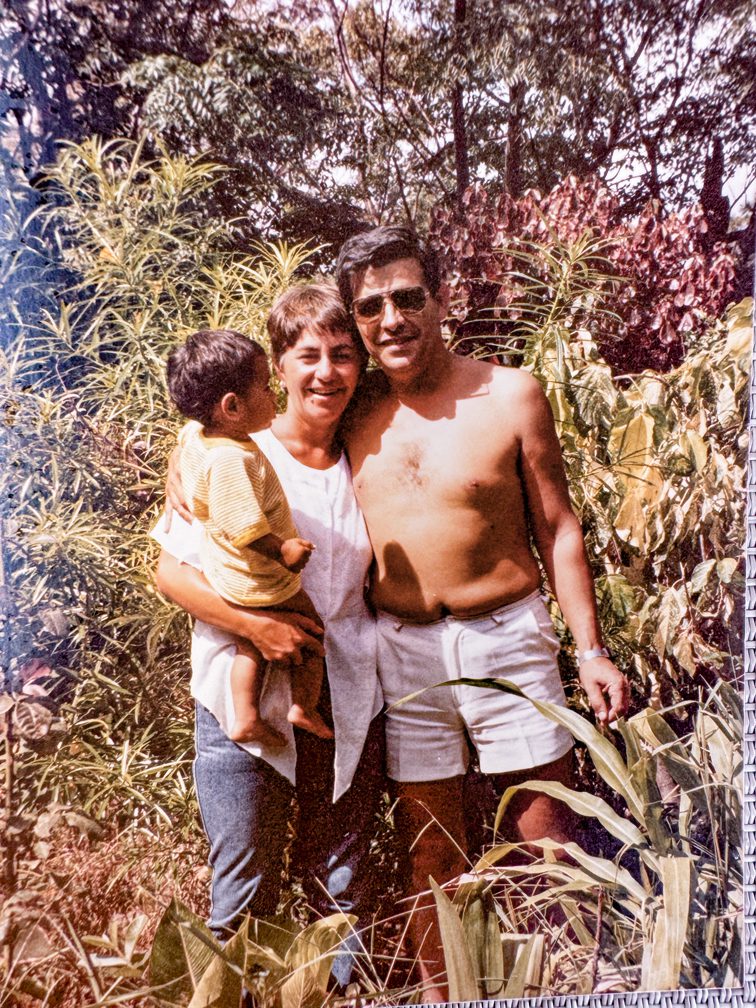

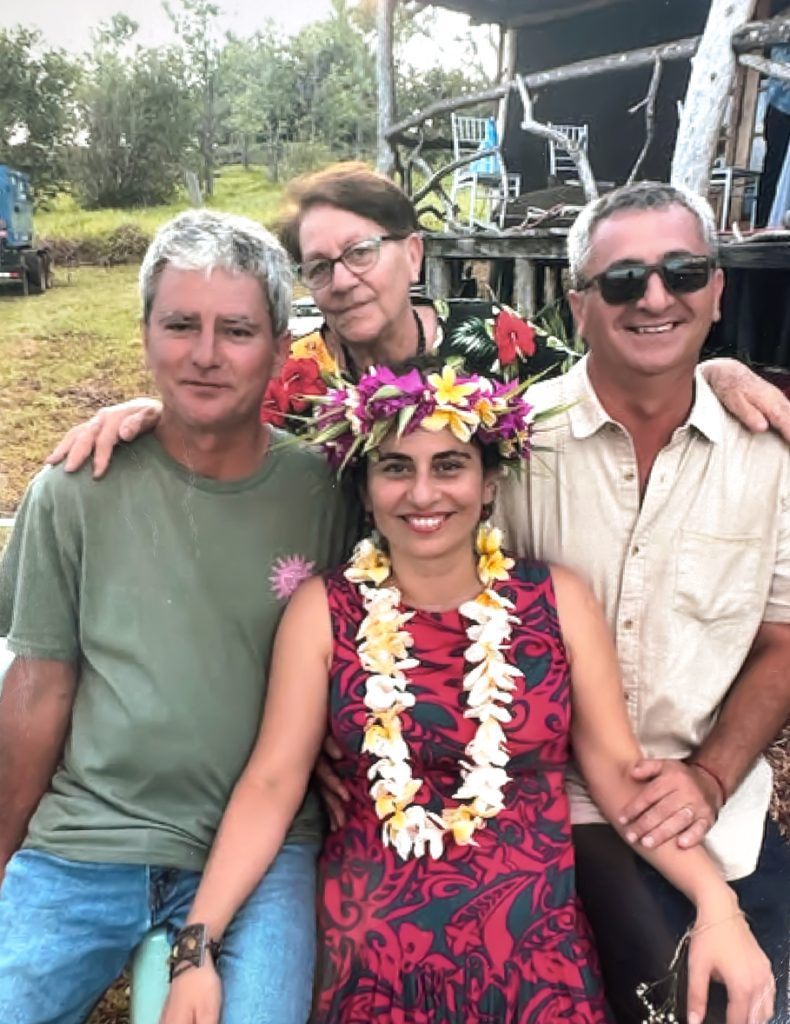

In Rapa Nui, everyone knows him as Oso “When I was a child, on a trip to the mainland, they brought me a teddy bear that was bigger than me. That didn’t exist on the island, so they started calling me Osito (Little Bear), and that’s how I stayed,” recalls Christian Madariaga Paoa. son of Ricardo Madariaga and Valeria Paoa Atamu, descendant of the Haumoana Tupa Hotu clan on his maternal side. His childhood was spent under the care of his grandparents, Amalia Atamu and Cristián Paoa, in a spacious and lively house where the ancient form of the Rapa Nui language was spoken.

His connection with education comes fron the roots. He is the great-grandson of Mariana Atamu, daughter of Recabarren, recognized as the island’s first traditional educator. Around 1935, in the absence of formal schools and after complaints of mistreatment by the only official who taught classes, Mariana took over the children’s education. “Papa Kiko and Elena Hotus told me that she was the first to teach the Rapa Nui language and culture,” says. That decision would establish a family teaching line that Christian maintains to this day.

He learned the Rapa Nui language since childhood, living for four years with his maternal grandparents while his parents’ house was being built. In that home, the language was a daily occurrence. Spanish was only spoken when his father arrived. Through everyday conversations, the tunu ahi, and visits from elders who shared stories, he naturally absorbed a profound and ancestral language. “That’s what’s missing today,” he reflects, aware of having inherited a linguistic treasure that is rarely heard anymore.

After finishing high school, Christian decided to study Physical Education at the Catholic University of Valparaíso. Together with his colleague Ángela Tuki Pakomio, they developed a thesis that broke new ground: a study of traditional Rapa Nui sports. They interviewed the wise , recovered documents, and developed a culturally relevant pedagogical proposal. “They congratulated us because it wasn’t a technical thesis, but an ethnological one,” he says.

In 1992, he began teaching on the island, promoting an education that highlighted Rapa Nui’s natural and cultural environment. At a time when sports were imported, Christian reintroduced ancestral traditions and was instrumental key in giving them a place at Tapati. Rodrigo Paoa, the event’s director at the time, called on him to transform the festival, which at the time was a continental spring celebration.

Oso helped create the foundations of the ancient sports still used today. “We were scorekeepers, judges, and builders of the foundations that are still used today,” he recalls.

At the same time, he incorporated Polynesian canoeing as an educational tool, along with Huilo Lucero and other leaders, when the first canoe arrived from the Kahu-Kahu o Hera corporation. “First we learned, then we taught. Today, canoeing is widespread. Seeing that fills me with pride.” He also applied this logic of learning by doing to the language. For him, the language must be experienced. He promoted immersion camps, field classes, games, songs, and competitions. “The language cannot be taught sitting in a room. It is learned by living.”

In 1999, he briefly assumed the general management of Tapati Rapa Nui. During that period, he promoted key improvements, such as the installation of the current horse racing circuit in Hanga Kura Kura.

Another of his paths has been music. Since he was a child, he dreamed of being a musician, inspired by Jorge Pakomio’s group. “Once, when I was eight years old, I told my mom I wanted to be a musician. She told me not to even think about it. But that idea stayed inside me.” Years later, she joined the groups Topa Tangi, where they recorded two albums: Moe Vārua and Hoko Hitu. On the album Ā’ati Hoi (2000), she contributed her own songs such as Kiva Kiva—a love song meaning “silently”—and the album’s eponymous song, inspired by horse racing. She also performed Ka ha’i mai koe, composed by her partner Ezequiel Tuki Zúñiga. The dynamic within the group was collaborative: those who composed also sang. This freedom was key to his artistic development.

During those years, he also started his own family. “I have two daughters, Vai ‘Iti Pakomio and Hatu Riva, and I’m married to Marcela Berríos, who is also a teacher. We are a close-knit family with values. My parents are still alive, and we’ve always been willing to help.”

In his more than three decades as a teacher, he guided several generations who now excel in different areas of Rapa Nui life. Athletes like Tumaheke Duran Veri Veri and Hugo Teave, musicians like Enrique Icka, and lawyer Tiare Aguilera Hey, passed through his classrooms. “I’m proud to see them now leading in their areas.”

In 2017, he took on a new challenge: leading, from the DAEM, the agreement between the Ministry of Education and the municipality for the revitalization of the Rapa Nui language in schools. His role as coordinator was key to advancing the training of traditional educators. Along with colleagues like Vicky Haoa, Carolina Pakarati, and Rodrigo Paoa, he raised a shared concern: who will take over?

One of the most important milestones of that stage was the implementation of a technical training program, in partnership with CEDUC at the Universidad Católica del Norte. Thanks to this effort, fifteen traditional educators—including Serafina Moulton, Manu Haoa, Alenn Lillo Araki, Hugo Teave Liempi, Cheche Angela Pakarati and Viviana Paoa— graduated as Advanced Technicians in Basic General Education in May 2025. This progress has allowed those who teach the language in the island’s schools to professionalize, ensuring that future generations have solid and well-prepared role models.

Today, all Rapa Nui educational centers have certified educators, native speakers, and up-to-date teaching tools. His life has been a fusion of knowledge: the preservation of ancestral sports, music, language, and living history. As an educator, musician, organizer, and father, Christian has built bridges between generations. “My heritage lies in education. In sharing without holding anything back. That’s what truly remains.”