By: Consuelo Martínez

A Life Forged in The Sea

Every morning, before opening Rapa Nui Dive Center, Boris Rapu spends a few minutes cleaning the area around Hanga Roa O’tai cove. “It’s not that I like cleaning,” he says, “it’s that this is my comfort zone. I live here more than at home.” In his dive center, the walls are covered with paintings and photographs of the seabed: turtles, corals, and fish; maps of the dive sites, regulators, fins, and masks. Everything around him breathes saltwater, history, and hard work.

He was born on April 23rd, 1981, at Hanga Roa Hospital. Son of José Jorge Rapu Haoa and Celia Tuki Chávez, he grew up surrounded by two lineages that are deeply rooted in the history of Rapa Nui. His grandfather, Anselmo Tuki Tepano, was a sculptor and cattle rancher; his grandmother, Celia Chávez Hey, traveled to Tahiti to buy materials for making necklaces and selling handicrafts. “She did the whole process, from collecting the shells to making the necklaces,” Boris recalls. “She did very well; they were a well-to-do family at that time.”

As a child, his life alternated between the sea and the countryside. “My childhood wasn’t bad. It was just complicated,” he says calmly. When his father, a nurse at the hospital, had to be away, he spent his days with his maternal grandfather. At Vaitea ranch, he learned to sleep outdoors, in the rain, tending to cows. “We’d improvise a tent with whatever we could find. That part of my life was spectacular.”

At thirteen, he decided to go with his father. He accompanied him on nighttime trips to the coast, walking without a car or motor. “We’d go to collect maíto or nanue. We’d eat that and give some away. We didn’t sell much.” Sometimes he’d get seasick, but it didn’t matter: the sea had already chosen him.“I always wanted to go, even though it made me seasick. I always wanted to be there.”

In 1997, while studying on the mainland, a pair of diving instructors came to his boarding school: Mary Salazar and Ramón Caballero, from the Viña del Mar Yacht Club. “We did the Open Water course. I was 17 years old. It was magical: I could breathe underwater,” he recalls. “The water was freezing, but it didn’t matter. It was like discovering another world.”

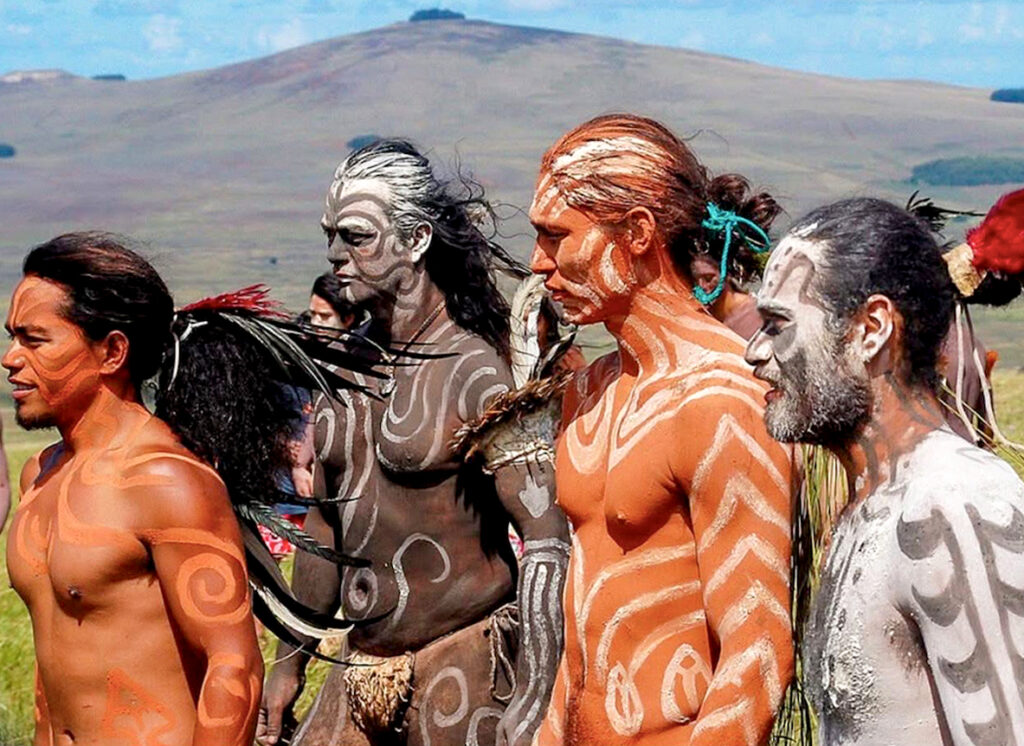

He finished high school and joined the Kari Kari ballet, a group that took him to international stages: France, Spain, Portugal, Tahiti. “Participating there was a dream come true,” he says. “But even though I traveled far, I always missed the sea.”

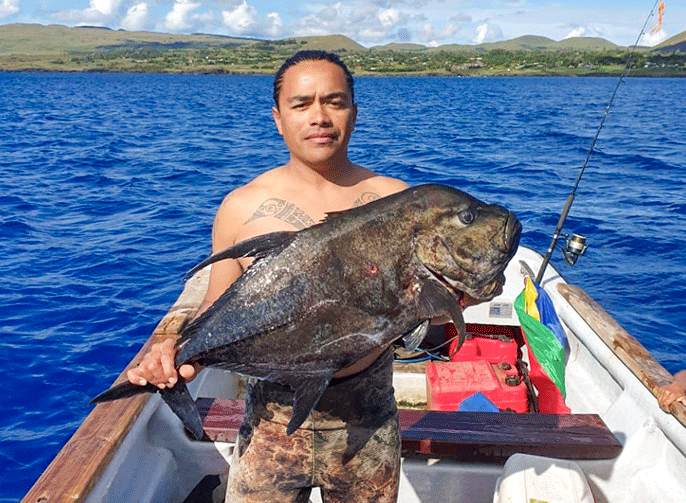

After two years, he tried to study Electrical Engineering, but the lack of scholarships and money forced him to return. “I had to come back by boat, as a kitchen helper. I didn’t have a penny.” By 22, he had already tried everything: dancer, tour guide, fisherman. In 2003, he started a small fish-selling business with friends. “We didn’t even name it. We just sold fish,” he says, laughing.

Learning from the Sea

His life took a definitive turn when he joined the Orca Diving Center, run by Michelle García, a pioneer of diving on Rapa Nui. “Joining Orca was a dream. Michel taught me so much, not just about diving, but about life,” he says. There, he learned about corals, turtles, and the impact of pollution. “Before, nobody gave the environment so much importance. But I understood that if we don’t take care of it, it will disappear. The more you take, the less there is.”

Over the years, Boris moved to Mike Rapu Dive Center, where he perfected his technique and earned his Dive Master certification. In 2014, with his savings and severance pay, he bought his first boat, the Matakau, and started offering marine tours. That same year, his personal life fell apart. The separation from his partner plunged him into a deep depression. “I went to the mainland, not knowing what to do. I was in a bad point” In 2015, he traveled to the United States, worked seasonal jobs, and returned with enough money to start over.

In 2017, together with a partner, he founded Rapa Nui Dive Center. “I had nothing, just a table and five wetsuits. But I was eager to succeed.” His drive was unstoppable. “I’m hyperactive. I did everything, like a ragtag circus,” he laughs. The center grew quickly: new equipment, more instructors, a secretary. “The other centers looked down on me, but then they realized I was real competition.”

The Storm Surge That Destroyed the Cove

The 2020 pandemic brought him to a sudden halt. The lockdown forced him to close the center and stay on the mainland with Daniela, whom he had known since 2017. “It was the worst thing that ever happened to me. I couldn’t see my children. I went a year without seeing them,” he says softly. Daniela, a nurse at the Clínica Alemana, kept the household going while he tried to cope with the confinement. “I was the nanny, I cooked, I cleaned. I cried a lot.”

In 2021, when he was finally able to return to Rapa Nui, a storm surge swept away some of his equipment and documents. “I lost almost everything.” But, as always, he got back on his feet. That same year he married Daniela, who is now also his right-hand woman in running the dive center. “We got married in the middle of the pandemic. It was spectacular. We were at the Sheraton and then in Cajón del Maipo. It was our respite.”

Boris has two children: Mahanua, 16, and Matakau, 9, both of whom live in Villarrica. “They are the most important thing to me,” he says. He speaks to them via video call every week. “Hearing them laugh gives me the strength to keep going. Everything I do, I do for them.”

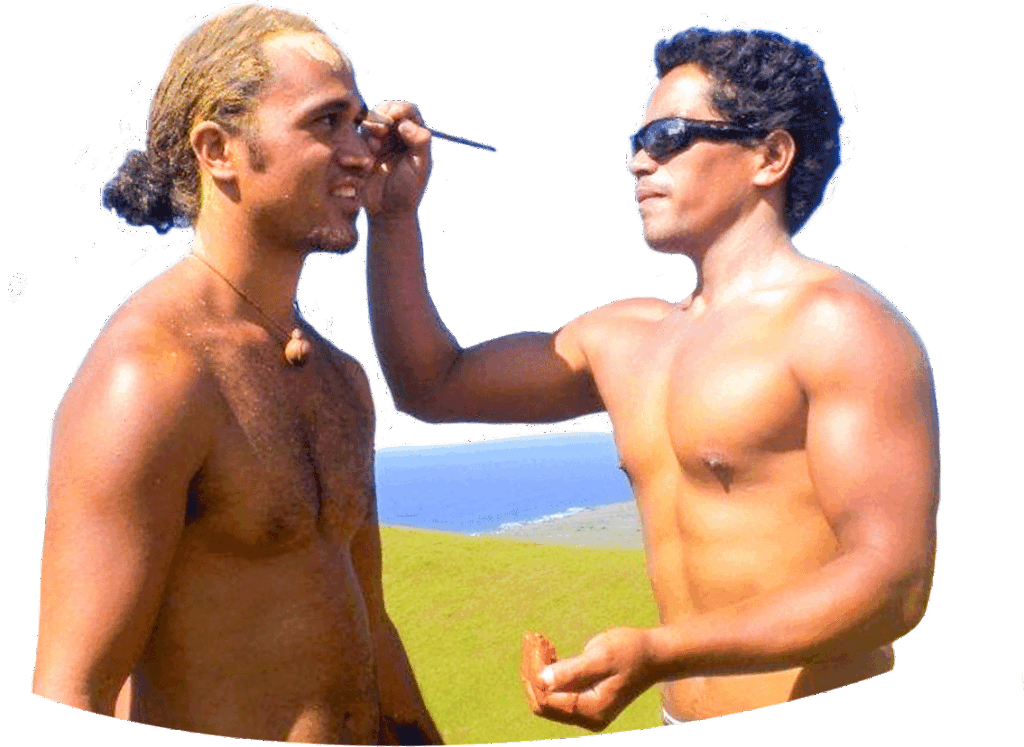

Boris with Uri Pate, Konturi Hito & Tera’i Atan – 2008

An Underwater Legacy

Today, Boris views the sea with a different awareness. “I’ve always been pro-coral and lobster conservation. I understand that we have to respect the cycles,” he says. At Rapa Nui Dive Center, he also works on environmental projects with IMEKO, which recycles cigarette butts collected in the cove. “We collect the butts, they extract the plastic and make things like eyeglass frames. It’s a small but real contribution.”

His motivation, however, goes beyond tourists and recreational diving. “I became an instructor not for tourism. I did it to teach children,” he says. His dream is for diving to be taught in the island’s schools as part of young people’s life plan. “I want to give an opportunity to those who can’t or don’t want to study abroad. This can be their life, their profession, their way of loving the island.”

He speaks of the sea with the devotion of someone who has lost and gained everything among its waves. “Before, I dived to survive. Now I dive to protect”, reflects Boris.